Authors:

(1) Anh V. Vu, University of Cambridge, Cambridge Cybercrime Centre ([email protected]);

(2) Alice Hutchings, University of Cambridge, Cambridge Cybercrime Centre ([email protected]);

(3) Ross Anderson, University of Cambridge, and University of Edinburgh ([email protected]).

Table of Links

2. Deplatforming and the Impacts

2.2. The Kiwi Farms Disruption

3. Methods, Datasets, and Ethics, and 3.1. Forum and Imageboard Discussions

3.2. Telegram Chats and 3.3. Web Traffic and Search Trends Analytics

3.4. Tweets Made by the Online Community and 3.5. Data Licensing

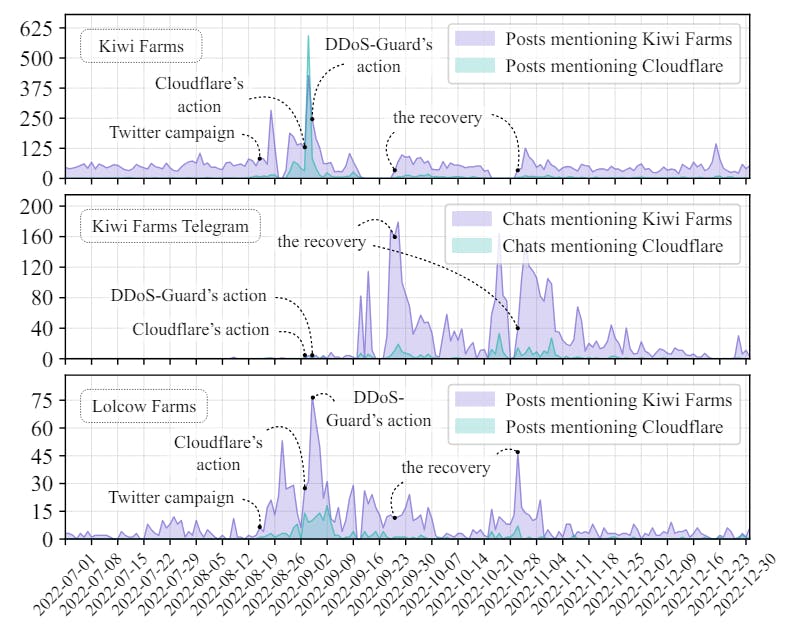

4. The Impact on Forum Activity and Traffic, and 4.1. The Impact of Major Disruptions

5. The Impacts on Relevant Stakeholders and 5.1. The Community that Started the Campaign

6. Tensions, Challenges, and Implications and 6.1. The Efficacy of the Disruption

6.2. Censorship versus Free Speech

6.3. The Role of Industry in Content Moderation

6.5. Limitations and Future Work

7. Conclusion, Acknowledgments, and References

6. Tensions, Challenges, and Implications

The disruption we analysed could be the first time a series of infrastructure firms were involved in a collective effort to terminate a website. While deplatforming can reduce the spread of abusive content and safeguard people’s mental and physical safety, and is already routine on social-media platforms like Facebook, doing so without due process raises a number of philosophical, ethical, legal, and practical issues. For this reason, Meta set up its own Oversight Board.

6.1. The Efficacy of the Disruption

The disruption was more effective than previous DDoS attacks on the forum, as observed from our datasets. Yet the impact, although considerable, was short-lived. While part of the activity was shifted to Telegram, half of the core members returned quickly after the forum recovered. And while most casual users were shaken off, others turned up to replace them. Cutting forum activity and users by half might be a success if the goal of the campaign is just to hurt the forum, but if the objective was to “drop the forum”, it has clearly failed. There is a lack of data on realworld harassment caused by forum members, such as online complaints or police reports, so we are unable to measure if the campaign had any effect in mitigating the physical and mental harm inflicted on people offline.

KIWI FARMS suffered further DDoS attacks and interruption after our study period but it managed to recover quickly, at some point reaching the same activity level as before the interruption. It then moved primarily to the dark web in May-July 2023. The forum operator has shown commitment and persistence despite much disruption by DDoS attacks and infrastructure providers. He attempted to get KIWI FARMS back online on the clearnet in late July 2023 under a new domain kiwifarms.pl, protected by their inhouse DDoS mitigation system KiwiFlare, but the clearnet version appears to be unstable.

One lesson is that while repeatedly disrupting digital infrastructure might significantly lessen the activity of online communities, it may just displace them, which has been also noted in previous work [90]. Campaigners can also get bored after a few weeks, while the disrupted community is more determined to recover their gathering place. As with the reemergence and relocation of extremist forums like 8CHAN and DAILY STORMER, KIWI FARMS is now back online. This supports the argument that truly disrupting online active platforms can be very challenging, much like the shortterm impact of shutting down cybercrime marketplaces [20], DDoS-for-hire services [14], [15], and other security threats combining efforts of both law enforcement and industry interventions such as botnets and fraudulent ad networks when botmaster is capable of momentarily deploying new modules to counteract the takedown [53], [54]. Deplatforming alone may be insufficient to disperse or suppress an unpleasant online community in the long term, even when concerted action is taken by a series of tech firms over several months. It may weaken a community for a while by fragmenting their traffic and activity, and scare away casual observers, but it may also make core group members even more determined and recruit newcomers via the Streisand effect, whereby attempts at censorship can be self-defeating [11], [91].

6.2. Censorship versus Free Speech

One key factor may be whether a community has capable and motivated defenders who can continue to fight back by restoring disrupted services, or whether they can be somehow disabled, whether through arrest, deterrence or exhaustion. This holds whether the defenders are forum operators or distributed volunteers. So under what circumstances might law enforcement take decisive action to decapitate an online forum, as the FBI did for example with the notorious RAID FORUMS [18] and BREACH FORUMS [92]?

If some of a forum’s members break the law, are they a dissident organisation with a few bad actors, or a terrorist group that should be hunted down? Many troublesome organisations do attract hot-headed young members, from animal-rights activists, climate-change protesters through to trade union organisers do occasionally fall foul of the law. But whether they are labelled as terrorists or extremists is often a political matter. People may prefer censoring harmful misinformation [93], yet taking down a website on which a whole community relies will often be hard to defend as a proportionate and necessary law-enforcement action. The threat of legal action can be countered by the operator denouncing whatever specific crimes were complained of. In this case, the KIWI FARMS founder denounced SWAT attacks and other blatant criminality [55]. Indeed, a competent provocateur will stop just short of the point at which their actions will call down a vigorous police response.

The free speech protected by the US First Amendment [94] is in clear tension with the security of harassment victims. The Supreme Court has over time established tests to determine what speech is protected and what is not, including clear and present danger [95], a sole tendency to incite or cause illegal activity [96], preferred freedoms [97], [98], and compelling state interest [99]; however, the line drawn between them is not always clear-cut. Other countries are more restrictive, with France and Germany banning Nazi symbolism and Turkey banning material disrespectful of Mustafa Kemal Ataturk. In the debates over the Online ¨ Safety Bill currently before the UK Parliament, the Government at one point proposed to ban ‘legal but harmful’ speech online, while not making these speech acts unlawful face-toface [43]. These proposals related to websites encouraging eating disorders or self-harm. Following the tragic suicide of a teenage girl [100], tech firms are under pressure to censor such material in the UK using their terms of service or by tweaking their recommendation algorithms.

There are additional implications in taking down platforms whose content is harmful but not explicitly illegal. Requiring firms to do this, as was proposed in the Online Safety Bill, will drastically expand online content regulation. The UK legislation hands the censor’s power to the head of Ofcom, the broadcast regulator, who is a political appointee. It will predictably lead to overblocking and invite abuse of power by government officials or big tech firms, who may suppress legitimate voices or dissenting opinions. There is an obvious risk of individuals or groups being unfairly targeted for political or ideological reasons.

This paper is available on arxiv under CC BY 4.0 DEED license.